On Reading Proust’s In Search of Lost Time

Published: 2025.12.18; Substack link

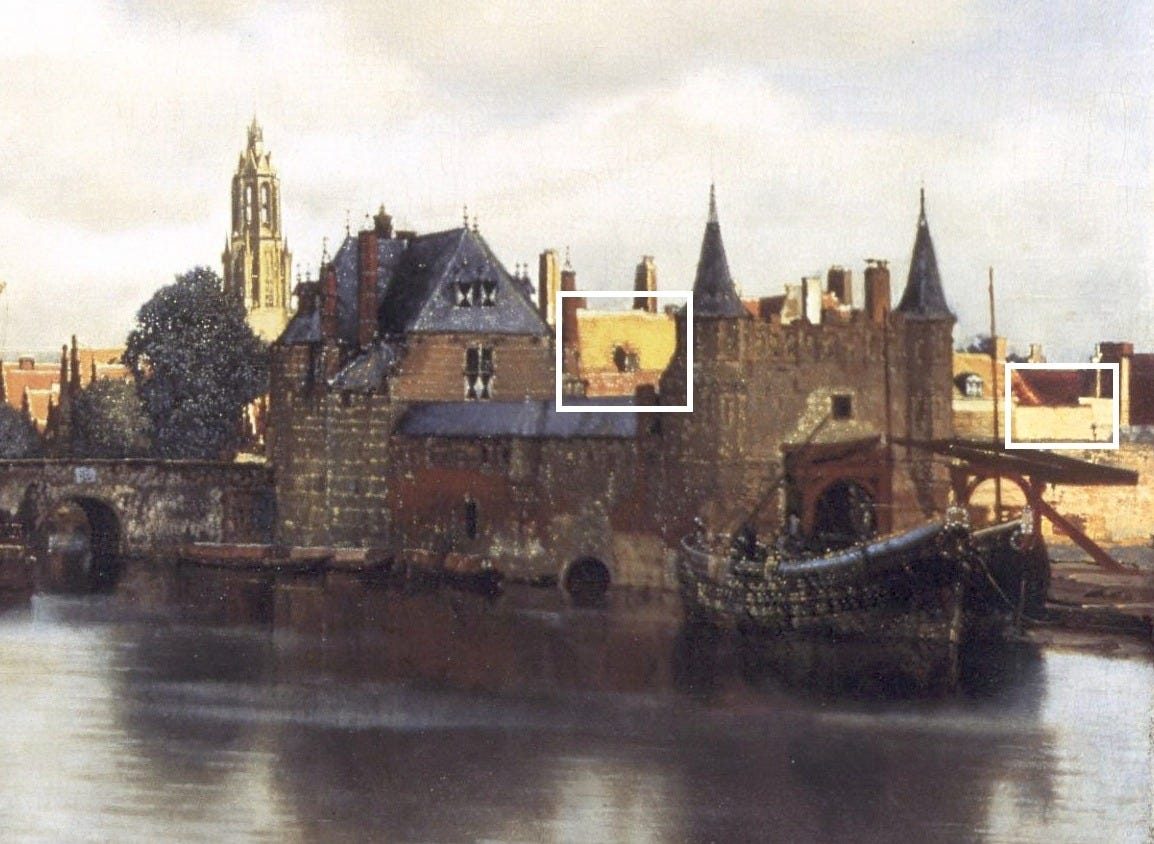

Vermeer, View of Delft (1660)

Vermeer, View of Delft (1660)1. Overture

For the first fifteen years of my reading life, whenever someone asked me who my favorite novelist was, I would tell them Tolstoy, because I’d read Anna Karenina. Now I am inclined to say it is Proust. I finished In Search of Lost Time a few weeks ago, and can’t stop thinking about it.

This is surprising. I read Book 1, Swann’s Way, a few years ago and although I liked it very much, I didn’t see why it was all the way up to the pinnacle of literature. I’m not the only one: after universal rejection, Proust had to pay publishers to publish his first couple of volumes; one of the publishers who rejected it said, famously: “I can’t imagine why anybody would read 50 pages about somebody falling asleep”.

Undertaking Proust was an act of faith. Reading even 10 pages of Proust tires you out as much as reading 100 pages of an ordinary writer. And unfortunately, to see why it’s so great, you have to finish all 7 books. I say unfortunately because the novel is 3,000 pages long and at times tough to read.

Yet not a word is wasted. It sounds paradoxical, but Proust is economical with his prose. He is simply trying to describe things that are extremely fine-grained and high-dimensional, and that takes many words. He is trying to pin down things that have never been pinned down before. And it turns out you can, indeed, write 100 pages about the experience of falling asleep, and find all kinds of richness in that experience.

I am not sure how to convey the delight of the prose. Try:

…the memories which two people preserve of each other, even in love, are not the same. I had seen Albertine reproduce with perfect accuracy some remark which I had made to her at one of our first meetings and which I had entirely forgotten. Of some other incident, lodged for ever in my head like a pebble flung with force, she had no recollection.Or:

I replied in a melancholy tone: ‘No, I’m not going to the theater just now, I’ve lost a friend to whom I was greatly attached.’ I almost had tears in my eyes as I said this, and yet for the first time it gave me a sort of pleasure to speak about it. It was from that moment that I began to write to everyone saying I had just experienced a great sorrow, and to cease to feel it.

2. The writing

I want to point out a few features of Proust’s writing.

First, constant use of analogies and metaphors. Everything is compared to physical, concrete objects, and sometimes he will use two or three different metaphors or analogies in succession to try and get at the same thing. Recall the “lodged for ever in my head like a pebble flung with force” from earlier. This is a form of extreme precision – he is always trying to get at the essence of the thing from multiple angles. (It is a curious fact about language that whoever seeks extreme precision is forced to use metaphor.)

As an aside, I tend to think that all great writers have this in common, and the frequency of it is especially striking when reading Homer, Shakespeare, and Dante.

The strongest oaths are straw / To th’ fire i’ th’ blood. (Shakespeare)There are many famous examples I could give here, but here is a funny one. Marcel finally meets an aristocratic object of his desire, Oriane de Guermantes:

Anger, which, far sweeter than trickling drops of honey, rises in the bosom of a man like smoke. (Homer)

She showered me with the light of her azure gaze, hesitated for a moment, unfolded and stretched towards me the stem of her arm, and leaned forward her body which sprang rapidly backwards like a bush that has been pulled down to the ground and, on being released, returns to its natural position.Like all of Proust’s descriptions, this is instantly vivid and precise.

Second, a clear-sightedness on human vanity and a total willingness to embarrass himself. There are passages in the Albertine sections which are shocking - such as the extended stretch, around 50 pages long, in which he describes watching her sleep - and, reading them, you start to understand that this was written by a dying man who did not care about anything apart from telling the whole truth in as merciless way as possible.

Third, hypotaxis in sentences. The opposite of hypotaxis is parataxis, which you often find in Hemingway, as in: "The rain stopped and the crowd went away and the square was empty." Each item here is side by side, simple, clean. The Bible often uses such types of sentences: “And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.”.

Hypotaxis, by contrast, describes sentences with many subordinate clauses, like nesting dolls. It is the domain of authors such as Henry James, or many of the great eighteenth century prose stylists such as De Quincey or Sir Thomas Browne. This type of sentence requires the utmost attention to parse, because clauses are often left hanging and modifying each other, and it is these cascading waterfalls of subordinate clauses that can make Proust’s long sentences hard to read.

This, for example, is the sentence that opens Book 2, which you will likely have to reread at least twice to understand:

My mother, when it was a question of our having M. de Norpois to dinner for the first time, having expressed her regret that Professor Cottard was away from home, and that she herself had quite ceased to see anything of Swann, since either of these might have helped to entertain the old Ambassador, my father replied that so eminent a guest, so distinguished a man of science as Cottard could never be out of place at a dinner-table, but that Swann, with his ostentation, his habit of crying aloud from the housetops the name of everyone that he knew, however slightly, was an impossible vulgarian whom the Marquis de Norpois would be sure to dismiss as—to use his own epithet—a ‘pestilent’ fellow.The whole experience of reading this requires your utmost attention the way that rock climbing does. But the benefit is that you inhabit a consciousness more sensitive and greater than your own; you gain the experience of thinking thoughts you were not capable of forming; and this eventually becomes delightful, especially since you get used to it as you go further on in the book.

3. The inner ring

This is a novel that describes its own creation. The plot of the novel, in very banal terms, is how Marcel Proust realizes his vocation in life, which is to be a writer. He realizes this after a series of false starts: first, he becomes a social climber, who thinks the goal of life is to be witty and artistic and in the best salons with the noblest people. Eventually he realizes this pursuit is hollow and never-ending, and once you’re in the “inner ring” it turns out that everyone is vain and boring. Then he falls grievously in love, and he thinks the goal of life is to be in love. But he’s possessive and constantly unhappy as a result, and eventually he grows disillusioned with that, too. Finally, he goes to a party, realizes he’s gotten old, and everyone around him has gotten old too, and he receives a series of shocks, or epiphanies, that force him to realize what he really needs to do is write his novel and put everything into it. So then he does that, which is the book you’re reading.

Told this way, the throughline of the book is the question of what you should want out of life, and one way of looking at the book is it shows how these desires are often constructed by people around you. This is an intensely Girardian theme, and Girard was heavily influenced by Proust’s novel, and may well have derived his core ideas from it. Desire in this novel is mimetic, and driven by scarcity, in a way that is constant and undeniable.

In the domain of romance, Proust’s narrator, and characters like Swann, only love people to the degree that they are (a) unavailable or (b) desired by others; as soon as they gain full possession of their lover, they get bored, and the love affairs in this book are just this cycle repeating again and again. There is no healthy love, just possessiveness and triangular desire. Most memorable is Swann’s obsession with the courtesan Odette, in book 1, a chapter often published as a small novel in its own right (“Swann in Love”) and an excellent, and approachable, gateway drug for those who want to understand what the fuss is about.

On other Girardian themes, there are also examinations of scapegoating: the Dreyfus affair, and people’s attitude to Jewishness/anti-semitism, are a constant theme in the book. (Proust was Jewish on his mother’s side.) Similarly, snobbery: in society, the best salons are the most exclusive, and these gradations matter more to the narrator the more trivial they are in reality. (See the narcissism of small differences.)

It is only through sickness and the shock of seeing everyone aging and dying around him, after the war, that Proust’s narrator is finally freed of all these desires and receives, as though through grace, a transmission of his true purpose in life. The novel can thus be thought of as a long conversion narrative in which art is the religion.

4. Memory

Part of the shock the narrator receives at the climax is a realization of the nature of memory. The narrator realizes that there is a type of involuntary memory, typically released by a sensory experience of some kind, which gives you a true recollection, a kind of full-body memory; this full-body memory is truer, more artistically valuable, more complex, than our usual memory which gets activated when you try and remember things. For Proust, ‘normal’ memory falsifies and flattens, and is too influenced by consensus reality: it is only through this richer, involuntary, sensory memory, often accessed through smell or taste, and usually unanticipated – it is only by pulling on that thread, that you get to the real, soft essence of yourself, and the artistic material that is in you. All true art comes from that murky essence. But because that murk is only unlocked through involuntary memory, you could in theory live your entire life not remembering it:

But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, still, alone, more fragile, but with more vitality, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls, ready to remind us, waiting and hoping for their moment, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unfaltering, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.This is why Proust becomes totally nocturnal in real life, because it is only at night that he can extract this raw material reliably. And this is what is famously dramatized by the bite of madeleine dipped into tea, which results in an entire chapter of his childhood coming back to him in a shudder:

And just as the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little crumbs of paper which until then are without character or form, but, the moment they become wet, stretch themselves and bend and take on colour and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, permanent and recognisable, so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann's park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and of its surroundings, taking their proper shapes and growing solid, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea.5. Tactical advice

A brief aside on tactics. This book is long, and I had to make it through – while running a company, no less – so here is how I did it.

First, translation: I picked Moncrieff and Kilmartin, revised by Enright, in the Random House three-volume set. There are the Penguin editions, but I did not like the idea of a different translator doing each volume, and I found Lydia Davis, who translates Book 1, unmusical and clumsy. The new Oxford World’s Classics translations look promising, but also suffer from the multiple translators problem. (That said, the Charlotte Mandell translation of Book 2 is amazing.)

Second, how to read it. The key is consistency. I made sure to always read 10 pages a day, which was usually a mix of (a) read a bit before going to bed (b) download a copy of the book on my phone and read a few pages on the way to work every day. The phone thing sounds weird – who reads Proust on an iPhone? - but this helped me stay consistent by widening the range of situations in which I could do the key thing, which was get a few pages in. I got the idea from this great Atlantic article, “Reading Proust on my Cellphone” (link). (I didn’t use audiobook, because I struggle to retain anything I hear on audio, but anything that helps a reader make forward progress is good.)

On weekends, I’d do longer stretches and knock out 100 pages a day. In this way the whole series took me about 6 months to read. I mostly did not read other books the whole time, which was the most painful part: but I figured this discipline would be necessary, otherwise I’d just get distracted.

There are some tedious stretches: in book 1, the Combray section goes on too long; there’s an interminable salon scene in book 3; and I found some of the endless misery and claustrophobia of book 5 and 6 hard to tolerate. But I promise you Book 7 (Time Found Again) is worth it, a pinnacle of literature, and moreover it justifies the entire series of books. Without book 7, the whole thing is just good; but book 7 is the payoff, book 7 helps you understand why he is doing all of it. I can’t really say more without spoiling it too much, but book 7 is where all the treasure is hidden. You must make it to book 7.

6. Modernity

Most discourse on the novel focuses on interiority, but Proust is as great a novelist about the exterior world, and the book is a fascinating record of the death of aristocratic manners, the rise of technology, the disruption of the war, Dreyfus, Jewishness, homosexuality, society and social habits, and more. This is, in part, a novel about the death of the old world, and the rise of the new.

In book 3, the narrator tries a telephone for the first time, and, after expressing awe at the miracle, immediately gets used to it:

The telephone was not yet at that date as commonly in use as it is to-day. And yet habit requires so short a time to divest of their mystery the sacred forces with which we are in contact, that, not having had my call at once, the only thought in my mind was that it was very slow, and badly managed, and I almost decided to lodge a complaint.In book 4, he sees an aeroplane for the first time:

Suddenly my horse reared; he had heard a strange sound; it was all I could do to hold him... then I raised my tear-filled eyes to the point from which the sound seemed to come and saw, not two hundred feet above my head, against the sun, between two great wings of flashing metal which were bearing him aloft, a creature whose indistinct face appeared to me to resemble that of a man. I was as deeply moved as an ancient Greek on seeing for the first time a demi-god... I wept... at the thought that what I was going to see for the first time was an aeroplane.And, in book 7, you get these lovely descriptions of the narrator walking through Paris during World War I:

The night was as beautiful as in 1914 when Paris was equally menaced. The moonbeams seemed like soft, continuous magnesium-light offering for the last time nocturnal visions of beautiful sites such as the Place Vendôme and the Place de la Concorde, to which my fear of shells which might destroy them lent a contrasting richness of as yet untouched beauty as though they were offering up their defenceless architecture to the coming blows.7. Proust’s philosophy

There is a philosophy in this novel that’s implicit but never fully outlined. It is something like: the inner life is all that matters. What’s stored in you, your deepest impressions, are what counts; these are when you live most vividly, and it is this ‘feeling aliveness’ that art is really supposed to channel and convey.

Note that often you don’t know what counts until later: e.g. the madeleine/tea moment, when he experienced it the first time, was not obviously important. It was only the later moment that ‘activated’ it as an important memory.

There is a passage I find memorable around the middle of the book, in which Marcel reads a (made-up) excerpt from the Goncourt brothers’ journal about a dinner party at the Verdurin’s salon, which he himself has been to many times. He becomes depressed after reading this, because the Goncourts, after attending this dinner party once, are able to produce many glorious pages stuffed with specific detail and precise, funny observations, and Marcel has been going to the exact same salon for months and is not able to say much about it at all beyond the fact that he finds it tedious. In this way Marcel learns that his own life, as banal as he feels it, can in fact be raw material for art if he learns to see, and examine, his own memory more deeply.

Proust can sometimes seem oddly Buddhist, e.g. at one point he refers to “the incurable imperfection in the very essence of the present moment”. But Proust’s philosophy is anti-Buddhist. For Buddhism, the (external) present is all that counts: for Proust, it is only the (internal) past. All value accretes in the memory and imagination, and ultimately all of life is to serve that, with artistic creation being the highest point of life, the transmutation of memory and imagination into an externalized object, the work of art. The present moment, paradoxically, doesn’t matter much, until later when you recollect it.

Even people are just material for art. This is the part of Proust’s philosophy that can seem anti-human: all of the people in his life are like puppets for him (and he says this explicitly in Book 7). This is clearest with his lover, Albertine: much of book 5 is him trying to control her and make her match the original, strong impression he had of her when he first saw her at the beach, and instead having to deal with the real, living Albertine-in-flux that’s right in front of him, stubborn and uncontrollable, with ‘fugitive’ and contradictory desires. And Marcel prefers her asleep, since then his imagination can take over entirely, and the present, real person in front of him does not interfere with the one he wants to see.

In a similar vein, Proust is against friendship to a shocking degree, describing it as “an abdication of duty”. In various parts of the novel, he describes friendship as a waste of time for the artist; only solitude spent in recollection and artistic creation counts. Solitude allows you go deeper into yourself, where you might draw out your own treasures. "The artist who gives up an hour of work for an hour of conversation with a friend knows that he is sacrificing a reality [i.e. art] for something that does not exist."

I don’t know if I agree with all of this – and I certainly don’t live my life this way – but I do understand it. And like any great work of art, Proust constantly works against his own stated purposes; and by putting it down in such exhaustive, beautiful detail, the book celebrates life. The weight of the specifics in this novel, the sheer richness of it, and the force of the epiphany in the final book marked my soul deeply.

Later in the book, one of the writers the narrator models himself against, Bergotte, is looking at this Vermeer painting, View of Delft, and he becomes obsessed with how, even in this large landscape, Vermeer paints the little patch of yellow wall towards the right of the painting so perfectly.

At last he came to the Vermeer which he remembered as more striking, more different from anything else he knew, but in which, thanks to the critic’s article, he noticed for the first time some small figures in blue, that the sand was pink, and, finally, the precious substance of the tiny patch of yellow wall. His dizziness increased; he fixed his gaze, like a child upon a yellow butterfly that it wants to catch, on the precious little patch of wall.Who knows if the religion of art was really enough for Proust; was he happy and fulfilled, after all? Better than any author before him, Proust exposes the hollowness of society, the inner ring, all driven by mimetic desire; and in love, too, he realizes he is chasing phantoms that will never satisfy him. It is not an exaggeration to describe the ending of the book as a sort of conversion, and Proust even slips in John 12:24:

'That’s how I ought to have written,' he said. 'My last books are too dry, I ought to have gone over them with a few layers of colour, made my language precious in itself, like this little patch of yellow wall.'

Meanwhile he was not unconscious of the gravity of his condition. In a celestial pair of scales there appeared to him, weighing down one of the pans, his own life, while the other contained the little patch of wall so beautifully painted in yellow. He felt that he had rashly sacrificed the former for the latter. ... He repeated to himself: 'Little patch of yellow wall, with a sloping roof, little patch of yellow wall.'

And often I asked myself not only whether there was still time but whether I was in a condition to accomplish my work. Illness which had rendered me a service by making me die to the world (for if the grain does not die when it is sown, it remains barren but if it dies it will bear much fruit), was now perhaps going to save me from idleness…But he does not go all the way. Ultimately, Proust locates his salvation in art and in his own memories, for him the most sacred thing of all; whereas Girard, like Dostoyevsky’s heroes, found his own salvation in Christ.

Photograph of Proust on his deathbed, by Man Ray.

Photograph of Proust on his deathbed, by Man Ray. My thanks to Tyler Cowen, Henry Oliver, and Jessie Li for reading a draft of this piece.